Florida government pension chiefs illegally deny access to public records designed to prevent pay-to-play public corruption

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Description | ||

Florida government pension chiefs illegally deny access to public records designed to prevent pay-to-play public corruption Pension officials stonewall releasing basic cash flow information on $17.9 billion in private equity and hedge fund investments for 4 months First published April 2, 2013 By Gina Edwards Watchdog City Press Florida government officials who oversee the state’s $132 billion pension fund for school teachers, law enforcement officers and other public workers are illegally withholding public records and violating key provisions of Florida law that were put in place to prevent pay-to-play public corruption scandals that have erupted in other state pension funds in recent years. Fee deals for middlemen – who are paid to steer billions of dollars in Florida pension business to certain firms selling secretive and high-risk, high-fee private equity investments – have been blacked out and kept secret by pension fund managers in response to a public records request by this Watchdog City Press reporter made in October.

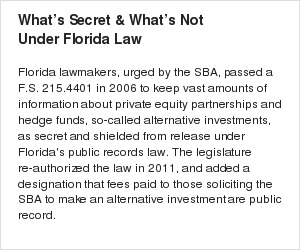

CarVal Investors LLC redacted the name of the placement agent and the name of the CarVal executive who signed the disclosure form. Separately, Florida pension managers at the State Board of Administration have stonewalled providing access to basic cash flow information on $17.9 billion in risky investments that’s specifically designated as public record, in response to an October 23, 2012 records request by this reporter. Initially, pension officials said they’d waive fees and provide the information in a matter of weeks. But after 4 months passed, they notified this reporter in mid-March that they would charge a $1,000 fee to provide basic information about what cash flowed back to taxpayers in pension fund coffers for these investments and when. The access delays and public records violations by Florida SBA officials come as federal regulators at the Securities and Exchange Commission are conducting a sweeping industry probe of high-risk private equity and hedge fund investments. Regulators are examining whether investors such as pension funds are getting ripped off on fees, conflicts of interest and bogus accounting that’s fraudulently inflated the values of secretive deals. Unlike public stocks and mutual funds with values that can be tracked moment-by-moment on a public stock exchange, private equity deal values are self-reported by the managers, and financial statements and prospectus details are kept secret from the public by design — even when it’s taxpayer money at risk. If bogus accounting fraudulently inflates the value of a pension fund’s investments, taxpayers and pensioners alike will feel the sting. Nationwide, public pension funds held more than $240 billion in secretive and risky private equity deals as of 2011, based on an analysis by this reporter of financial statements of 88 pension funds. Middlemen fixers are at the center of public corruption cases involving the California and New York public pension funds, where top pension officials have been accused of steering pension business to certain risky and secretive private equity deals in exchange for gifts and bribes. A federal grand jury indicted the former CEO of California’s public pension fund on March 18 in connection with his dealings with a private equity investment middleman who was paid $70 million in fees to secure pension fund business. New York’s elected state comptroller served a year in prison after pleading guilty to pension fund corruption charges in 2011. In the wake of public corruption scandals at public pension funds in California and New York, Florida began requiring the disclosure forms in December 2009. In Florida, of the 40 firms using middlemen, or placement agents, to solicit state pension business in private equity and hedge fund investments since December 2009, 29 firms asked that disclosure forms be blacked out and kept secret specifically in response to the public record requests made by this Watchdog City Press reporter on Oct. 8, 2012. Florida’s First Amendment Foundation President Barbara Petersen says the middleman fee redactions appear to violate Florida law, which specifically designates fees paid to those soliciting pension fund business as public record. Florida government officials at the SBA that oversees the pension fund took more than 3 months to produce the requested documents, a process dragged out because government officials first asked the firms if they wanted to black out parts of the public disclosure forms and claim them as confidential proprietary business information. That confidential designation was created by a 2006 Florida law that makes vast amounts of information secret about the pension fund’s private equity and hedge fund and other so-called alternative investments. But the law designates certain basic information about these investments as public record, and this reporter asked only for information that’s specifically designated as public record under the law in the Oct. 23, 2012 request. Ultimately it’s the job of Florida’s pension managers at the SBA — who answer to trustees Gov. Rick Scott, Chief Financial Officer Jeff Atwater and Attorney General Pam Bondi — to uphold access to public records. Florida SBA Executive Director Ash Williams declined an interview request by this reporter. In a written statement, SBA spokesman Dennis MacKee said the Florida pension fund’s alternative investments, which includes private equity, are the pension fund’s second-best performing class of investments behind real estate. (See related story) Secret by law Private deal agreements, prospectuses and marketing materials used to pitch the SBA pension managers, who are entrusted with broad power to make investment decisions, are allowed to be kept secret under the 2006 law, Florida statute 215.4401. So the back-up financial detail that could give taxpayers and pensioners confidence that the deals are legitimate — and that these investments are worth what the private equity and hedge fund managers say they’re worth — are allowed to be kept secret. The law keeps these public records a secret for 10 years — after the SBA ends the deal or sells the investment. But basic information about private equity, hedge fund and similar investments — which are known as alternative investments in industry jargon — is required to be disclosed as public record under the law. The Florida legislature re-authorized the 2006 secrecy law in 2011. At that time, a subsection of the law was added that specifically states that compensation, fees, or expenses paid to people or firms soliciting pension fund business in alternative investments can’t be deemed confidential and withheld from the public. In other words, the names of middlemen and the fees paid to them is public information. Show Us the Money For 4 months, Florida pension officials at the SBA have stonewalled a separate public records request made by this Watchdog City reporter on Oct. 23, 2012 for basic cash-in and cash flowing back information from the $18.7 billion that the Florida pension fund has contributed to private equity and hedge funds deals. The requested cash-flow information, which is specifically designated as public record under Florida law, would allow public scrutiny and an independent analysis of the SBA pension chiefs’ track record in managing the $17.9 billion in public money that’s currently invested in these risky, and secretive private deals. Initially, SBA officials offered to provide the cash flow records and other information that’s specifically public record to this reporter in a matter of weeks and waive a $4,600 fee to cover staff time, saying the agency saw public benefit in compiling the records as requested. The public records request by this reporter only asked for basic information about the pension fund’s private equity and hedge fund investments that is specifically designated as public record under Florida law. SBA officials produced one batch of documents in November. But after more than 4 months of delays, SBA officials sent a letter in mid-March, saying they wouldn’t release 16 years’ worth of cash distribution data — money flowing back to pension fund coffers — unless this reporter pays $1,037 to cover 43 hours of staff time to produce the public information. It’s not clear why the SBA can’t pull this public information out of its accounting system in a matter of hours since it keeps the information on a cumulative basis and produces cumulative reports regularly. The SBA provided fees broken out by investment spanning 20 years in “several hours” and provided that with documents sent with the mid-March response. The detailed cash distribution data is needed because the timing of when money flowed in and cash was taken out of these investments would give a precise picture of what returns these risky deals have produced for taxpayers and the more than 600,000 teachers, law enforcement officers and public workers who are counting on the pension fund for their retirement. In the mid March response, the SBA did provide a profit and loss chart for 6 closed-out private equity deals. The chart shows collective gains of $351.5 million. Those profits sound good, but that’s not the whole picture. The six limited partnership deals kept pension money locked up for between 10 to 15 years. An analysis shows that the SBA could have made $1 billion more than it did if pension chiefs had invested the $863 million in taxpayer money in a less risky, low-fee stock market index fund instead of the high-risk, high fee private deals. (See related story) Along with refusing to disclose the names of some middlemen and the fees they collected, SBA officials also ignored altogether this reporter’s request for disclosure of the names of the executives in the firms who put the deals together and received the $18.7 billion in taxpayer money. The names of these principals involved with alternative investments are also specifically designated as public record under Florida law.

FS Equity Partners VI disclosed that it paid a placement agent $1 million to set up two meetings with state pension managers. One middleman disclosure document the SBA turned over that contains no redacted information sheds light on the high stakes and competition to get pension fund business: That firm paid $1 million just to get an audience with Florida pension managers. FS Equity Partners VI LLC, revealed on its 2010 disclosure form that it paid $1 million to Credit Suisse First Boston Inc. to arrange two meetings with three SBA employees in 2003 in connection with an earlier deal. After the meeting, SBA employees subsequently invested $50 million in pension money in one of FS Equity Partners’ funds in 2004 and later committed $75 million to a separate deal beginning in 2009. Annoying questions Securities laws governing public companies that take money from investors and that trade on open stock exchanges were designed to make information transparent to buyers and sellers in the public financial markets so investors have confidence in fair play. This transparency has greased the gears of capitalism since the Great Depression. Fake Returns The SEC announced on March 11 that Oppenheimer & Co. agreed to pay a $2.8 million fine in connection with charges that it inflated the value of private equity investments in marketing materials. "Honest disclosure about how investments are valued and how performance is measured is vital to private equity investors," said George S. Canellos, acting director of the SEC's Division of Enforcement in a statement. "This action against Oppenheimer for misleadingly writing up the value of illiquid investments is clear warning that the SEC will not tolerate lax disclosure practices in the marketing of private equity funds." But private equity doesn’t play by those rules. Much of the private equity industry has cloaked itself in layers of secrecy that it, in turn, requires of its investors – including public pension funds. Private equity firms typically require investors to sign confidentiality agreements and promise to keep secret the prospectuses that spell out deal details and the contracts that govern fee arrangements and pay-outs. When it comes to public pension funds, though, this secrecy keeps pensioners and taxpayers from scrutinizing the ways in which billions of taxpayer dollars are being deployed by private equity firms to generate profits for their investors and the private equity firms putting the deals together. Wizards Behind the Curtain

Private equity managers — the financial wizards known for buying and flipping companies using mountains of other people's money — have an open secret on Wall Street that appears mostly lost on the average taxpayer. Taxpayer-funded public pension funds are private equity firms' biggest customers. The private equity industry has control of an estimated $240 billion or more in taxpayer-funded public pension fund money, based on an analysis of state data by Watchdog City Press reporter Gina Edwards. Federal regulators at the Securities and Exchange Commission are conducting a sweeping industry probe of high-risk private equity and hedge fund investments. Regulators are examining whether investors such as pension funds are getting ripped off on fees, conflicts of interest and bogus accounting that's fraudulently inflated the values of secretive deals. See the in-depth Special Report "Trusting Wall Street's Wizards Behind the Curtain." With the industry under scrutiny, the Private Equity Growth Capital Council trade group has released a series of reports in the past six months as part of a public relations campaign to defend the industry, saying private equity firms have provided healthy investment returns to public pension funds and pumped billions into economy to help companies grow. Here’s how private equity funds work: Private equity firms collect vast pools of money from investors such as pension funds, endowments, insurance companies and wealthy individuals and in-turn use the money to buy or prop-up private companies or to take over public companies. In the case of takeovers, called leveraged buy-outs, the private equity fund may put down some money and then borrow a lot of money to make the purchase, oftentimes saddling the takeover company with mountains of debt. In other cases, private equity firms supply venture capital money and management expertise to help young companies grow. What companies are bought — and who benefits — isn’t transparent like the financial dealings of public companies that are required to disclose large amounts of information in SEC filings on the Internet. Lisa Lindsley, director of Capital Strategies for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees, the 1.6 million member union has criticized the secrecy of private equity investments held by public pension funds. At its national convention in June, AFSCME adopted a resolution calling for more transparency and less secrecy surrounding private equity investments. “There’s this attitude that ‘You definitely want to invest with us because we have the secret sauce, but if you keep asking these annoying questions then you can’t invest with us,’” Lindsley says speaking generally about the industry. Sunshine as disinfectant Pay-to-Play: California pension chief accused of steering business to private deals for gifts and bribes Fees paid to private equity middlemen and disclosure forms are at the heart of a pay-to-play corruption case against the former CEO of California's public pension fund, known as CALPERs, and a placement agent middleman who received $70 million to solicit pension business.

Buenrostro On March 14, a grand jury indicted Federico Buenrostro Jr., the former CEO of California's pension fund on fraud charges that include allegations that he and a middleman forged placement agent disclosure forms to conceal their influence peddling arrangement. The private equity firm Apollo Global Management had begun requiring placement agent disclosure forms in March 2007 to comply with federal securities laws, according to the indictment. Buenrostro, as CALPERs chief officer, signed off on vague placement agent forms and forged one form so the middleman could collect $14 million in fees from Apollo, the indictment says. Buenrostro's attorney, William Kimball, declined to comment. New York's elected comptroller, Alan Hevesi, served a year in prison after he pleaded guilty in 2011 to taking bribes and gifts in a pay-to-pay corruption scandal involving New York's state pension fund. Following the scandals that broke in New York and California, SBA Executive Director Williams announced Florida’s placement agent disclosure policy in an SBA press release saying that “Sunshine is the best disinfectant,” quoting U.S. Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis. This reporter had one recorded interview with SBA Communications Manager John Kuczwanski on Oct. 5, 2012 and asked for the placement agent disclosure forms, and subsequently sent the request in writing on Oct. 8. Since that day, Florida SBA officials have refused repeated interview requests and will only answer questions about the pension fund’s alternative investments from this reporter in writing. In October, the SBA required this reporter to pay $242 up front for staff time to ask the firms if they wanted to redact information before the government body would produce any public records. Florida’s First Amendment Foundation President Petersen says such upfront service type fees are questionable. And she said the redactions of fees paid to middlemen placement agents appear to violate Florida law, which specifically designates fees paid to those soliciting pension fund business as public record. Of the 29 funds that asked the SBA to black out information on the middlemen placement agent forms, all filed sworn declarations saying the information isn’t readily available from other sources and that release of such information would hurt their business operations. Petersen says firm executives claiming confidentiality without cause could be charged with perjury depending on the circumstances under Florida law. Ultimately, Florida SBA officials are required to uphold public access laws, Petersen says. Blacked out Based on the placement agent forms with no redactions, records show these middlemen provide a variety of services, including sales and marketing, negotiations and in some cases production of the deal prospectus. Who made the pitches to pension fund managers can be significant if deals were fraudulently sold or misrepresented. "If there are risks that aren't adequately disclosed then whoever's making the sales pitch can have potential legal liability," says investor advocate Jason Doss, a securities attorney who is the president-elect of the Public Investors Arbitration Bar Association. One company that responded to the SBA, Kelso & Co., asserted that its entire placement agent disclosure form is confidential proprietary business information and should be kept secret. Still others, like Bayview Asset Management LLC, claimed only the specific fee amounts as confidential, but didn’t ask for confidentiality for other information like the bios of the placement agents and their regulatory report cards.

Willis Stein & Co., on its hand-written form, said it couldn't disclose fees paid to its placement agent because of a confidentiality agreement. Another firm, Willis Stein & Partners, submitted handwritten answers on its disclosure forms to the SBA in 2010 and 2011. The executive who filled out the form refused to provide information to the SBA about how much in fees it paid its placement agent, Donaldson Lufkin & Jenrette, saying the information was subject to a confidentiality agreement. The SBA’s placement agent disclosure policy states that any change to an existing agreement with an outside investment manager triggers the placement agent disclosure policy requirement. SBA spokesman MacKee said in a written statement that the SBA director has discretion under the policy and can evaluate the requirement on a case-by-case basis. The relaxed rule for Willis Stein was signed off on by the previous inspector general and later the SBA’s compliance department in 2011, MacKee said. He provided a copy of a revised January 2013 policy. In the case of Global Infrastructure Partners II, the firm disclosed on its form it paid a “flat fee” to placement agent Credit Suisse for introductions to investors like the SBA but it didn’t say how much. MacKee said Global Infrastructure Partners appeared to have misinterpreted the requirement to be specific. “Generally our agreements allow us to go back to the manager to rectify any errors or omissions of this type which we are now in the process of doing,” MacKee said. CarVal Investors LLC claimed its two disclosure forms should be confidential and blacked out all information including the name of the placement agent — and the executive signing the form. The firm revealed it paid the unnamed middlemen a fee of .35 percent of the total committed to two of its hedge funds by the SBA. Those secret fees could amount to $1.1 million based on SBA commitments of $95 million and $225 million to two CarVal hedge funds. On documents filed with the SEC in February, CarVal reports that it no longer pays fees to placement agents in connection with its hedge funds. Republican House Rep. Mike Fasano, R-New Port Richey, has attacked the secrecy surrounding Florida’s pension fund investments in hedge funds and private equity.

Mike Fasano, R-New Port Richey Fasano, a stockbroker by training, says information put out to the public is loaded with confusing Wall Street jargon. Because of what’s broadly kept secret and dubbed “confidential proprietary business information” the public has no way to know, even in hindsight, what’s driving the investment decisions being made. “It’s all got to come to an end,” says Fasano of the secrecy. He says the secrecy is designed to benefit the SBA and the private firms, but it’s hurting taxpayers and the people who are relying on the pension fund for their retirement. In 2011, Fasano filed a public records request seeking information about alternative investments held by Florida’s pension fund. The SBA sent the state lawmaker, serving in the Florida Senate at that time, a bill for more than $10,000 for the public records. Following negative coverage by Florida newspapers including the Tampa Bay Times and a scolding by Chief Financial Officer Atwater and Attorney General Bondi, the SBA dropped the fee. It took months for Fasano to get the records, and what he got has hundreds of pages with much of it blacked out and redacted. “How do they determine what to invest in,” Fasano says. “What made you decide to make a $150 million investment?” The public doesn’t know how decisions are being made about billions of tax dollars and people’s retirement, says Fasano. “It’s happened because we’ve allowed it to happen.” Get the Full Story! for $0.99 |

| Other Images | ||||||||

|

| Paid Story |

| You don't have permission to view. Please pay for this story to gain access. |

| Paid Video |

| You don't have permission to view. Please pay for this story to gain access. |

| Ask a question or post a comment about this story | ||||||

|

||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

CarVal Investors LLC redacted the name of the placement agent and the name of the CarVal executive who signed the disclosure form

CarVal Investors LLC redacted the name of the placement agent and the name of the CarVal executive who signed the disclosure form Triton Managers IV Limited blacked out a description of the fees paid to its placement agent.

Triton Managers IV Limited blacked out a description of the fees paid to its placement agent. Willis Stein & Co., on its hand-written form, said it couldn’t disclose fees paid to its placement agent due to a confidentiality agreement

Willis Stein & Co., on its hand-written form, said it couldn’t disclose fees paid to its placement agent due to a confidentiality agreement P2 Capital Partners blacked out fees paid to its placement agent.

P2 Capital Partners blacked out fees paid to its placement agent. FS Equity Partners VI disclosed that it paid a placement agent $1 million to set up two meetings with state pension managers.

FS Equity Partners VI disclosed that it paid a placement agent $1 million to set up two meetings with state pension managers. Ash Williams

Ash Williams Letter to Gov. Rick Scott

Letter to Gov. Rick Scott Federico Buenrostro Jr.

Federico Buenrostro Jr.